Have you ever wished you could see exactly what other people are thinking? Have you noticed you can set your watch by the times you are laser-focused verses when you are easily distracted? Have you ever felt an emotion you weren’t expecting (like fear or excitement) and wondered why?

In this four-part series, we’ll review some of the latest brain science and how it affects our roles as leaders. You may be wondering, “why the sudden interest in neuroscience?” In recent decades, technology has given us the opportunity to learn about the brain in ways that have broader applications for our daily lives. Practitioners of coaching and consulting find brain science to be a highly useful tool when working with our clients!

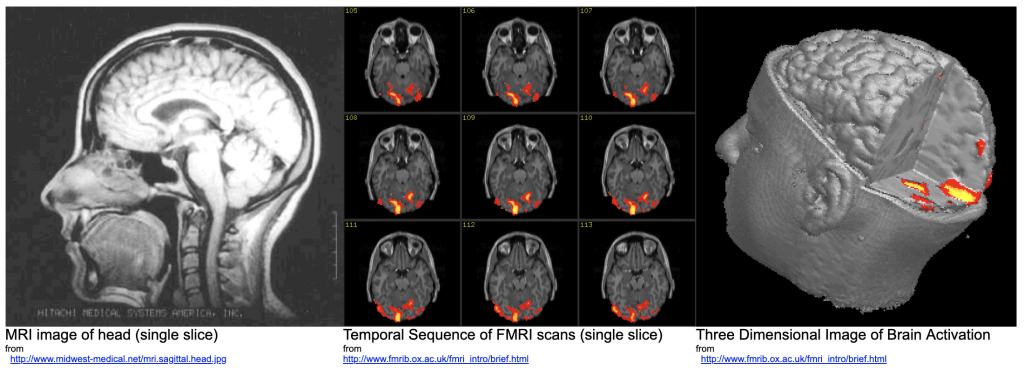

From the late 1970’s, the best way to look at the brain was the MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) machine. An MRI uses magnets and radio waves to create images of the body and is useful for looking for tumors or tears or ‘anatomical structure’ – but the MRI has limitations. In the 1990s, scientists introduced the fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging), which looks at ‘metabolic activity’ in the body. The fMRI can see blood flow and uses it to map which parts of the brain are active when a person is thinking about or doing something. This was a huge leap forward for neuroscientists, who are able to use that activity roadmap to learn more about the way humans think, feel, and process information. Turns out this is also a great roadmap to successfully managing our brain’s natural processes to our advantage.

A Pioneer in Neuroleadership

Dr. David Rock is a pioneer in the study of the convergence of neuroscience and leadership. He coined the term “Neuroleadership” and is a sought-after expert on the subject. In his book, Your Brain at Work, one section outlines how we can create better conditions for our higher-level thinking and productivity at work. He uses a stage analogy to describe the part of the brain where big ideas happen – the prefrontal cortex. In the PFC, we make judgements and decisions, problem solve, and plan ahead. If the prefrontal cortex is a stage, on that stage, there is only room for 3-4 “actors”, or pieces of information the brain can evaluate at one time. That same stage only has one spotlight and different ‘actors’ (ideas or problems) compete to stand in it. The spotlight is our brain’s ability to focus.

Imagine if you were at the theatre and four actors were on stage shouting their lines at the same time. The spotlight would bounce back and forth between them, but you wouldn’t know who to pay attention to. Our brains do the same thing, especially when we’re trying to multitask! While humans can balance up to 4 bits of information at a time, we can really only remember one of those pieces of information later. Therefore, we have to help the ‘director’ get the ‘actors’ in order so we can think and process the information they hold most effectively. Dr. Rock has a few strategies to help us understand the ‘actors’ better.

First, we should notice when we are switching tasks rapidly…

(Think scanning emails while in a meeting, watching TV or at your child’s game.) Switching tasks (aka multi-tasking) actually reduces our available mental energy, so it’s better if we don’t do it. Instead, we should create blocks of time for each task we need to complete. For example, we could spend 20 minutes on emails, 20 minutes for editing that report, followed by 20 minutes for a performance evaluation with Jack from the Ops team. Using a task sequence strategy is like giving each actor solo time in the spotlight. That time is clear, focused and more meaningful and memorable.

Second, Rock suggests we ‘chunk’ information into related parts,

to help us hold on to more at a time. A phone number is a very simple example of chunking – we could remember the area code as one ‘chunk’ then the next three digits as a chunk, then the last four digits as two chunks, which reaches our maximum of four chunks. Chunking is so effective at tricking our brain that over the course of a two-year experiment, one grad student was able to use the strategy to remember a number sequence 80 digits long – the equivalent of 7 phone numbers!

Chunking works because our brain craves patterns – we look for ways to connect bits of information and then use those connections to form meaningful groups of information that are easier to process than those pieces of information would be alone. Chunks are the little choruses on our stage, singing related bits of music so we can process it as a whole and compare it with other small choruses of information.

Third, Dr. Rock recommends we pay attention to the times we perform best.

Just like a theatre that has closing and opening hours, the prefrontal cortex needs time to dim the stage lights. For most people, it is better to perform the most complicated tasks at the beginning of the day when the brain is fresh and rested. Think of your computer – when you first turn it on, it hums with efficiency. At the end of the day, when you have 15 applications and 40 windows open and you’re running a video call, the computer gets hot and slows down. Each of us is different though, and personal observation is the best way to see our most effective working times. Note when the ‘director’ can’t seem to keep the ‘actors’ in order – ie, you’ve become much more easy to distract and it’s harder to stay fixed on one task. This is a sign your prefrontal cortex is tired and needs rest. These are the times you should push off complicated tasks and switch to tasks you can do on autopilot.

TIP: We highly recommend the entire book, but if you’re short on time, this video is a fun visual summary of this analogy!

Get Your Prefrontal Cortex in its Happy Place

Another strategy we can use to turn on our prefrontal cortex is to get ourselves in the right state of mind. Jeff Nally, an Executive Coach and valued colleague, specializes in using brain science in his sessions with clients. He told us that in order for the PFC to function at its best, it must be in a neutral to slightly positive state. Why? When the prefrontal cortex is in a neutral to slightly positive state other parts of the brain can relax and let the PFC work. To relax, the rest of the brain must be sure there are no active threats or needs to address – a neutral state sends that message that everything is OK. To get ourselves in that state it is important to ‘turn off the noise.’ One tactic Nally uses is to ask his clients to try 30 minutes of yoga or 30 minutes of mindful meditation before their session starts. He shared that often, executives are skeptical and say they can’t spare that kind of time. After they meet, he notes, they see “…it immediately puts their brains in that state so they can have their own insights and ideas, and no kidding – at the end of the first session they’re like ‘I see what you did there. That’s not really hard. I know how that feels… I know when I’m not in the best state to have a new idea. And I know when I’m more likely to have one.’” They see the value of taking a few minutes to get their mind in the right state first, because it dramatically improves the value of their time in coaching.

As a leader, you can use these tactics to help your team be more productive. To start, use these strategies yourself and teach your team to do the same. Your good practices will be the genesis of a culture shift that will help everyone have more productive days and more ‘aha’ moments.

Create an environment that fosters successful use of these strategies.

Think about the distractions and competing demands on your team’s time and try to reduce them. Give your team space to try chunking, task sequencing, and quiet meditation. Evaluate your own behavior – are you sending your team the message that they always have to be ‘on’ and must pay attention to every need the second it arises? Have you ever sent a Slack message, then stomped to the recipient’s cube 10 minutes later and asked why they haven’t responded? Does your team get the message that breaks are important or is it taboo to ‘take five’? Is your team hard-pressed to find a spot to sit quietly for a few minutes before a brainstorming session to get in the ‘right state of mind’ for creative activity? Do you IM your team members and demand answers at all hours, including the evening and early morning? Are there monitors in every break room and conference room, competing for your team’s attention?

If any of the above sound familiar, you may be unintentionally burdening your team and complicating their ability to successfully use their highest thinking.

In the next blog, we’ll look at ways we can reduce the stresses, distractions and unpleasant emotions that can hijack our thinking.

Be sure to let us know if there is anything you’d like to know about using your brain better at work. We may include your question in an upcoming post!

In the meantime, try some of these strategies and let us know how it goes.

All the best,

Great article. I often find myself thinking that I am not being effective because I have so much on my mind. I have heard this info before but the actor analogy really brought it home. Going to give these strategies a try.

Hello. remarkable job. I did not expect this. This is a splendid story. Thanks.